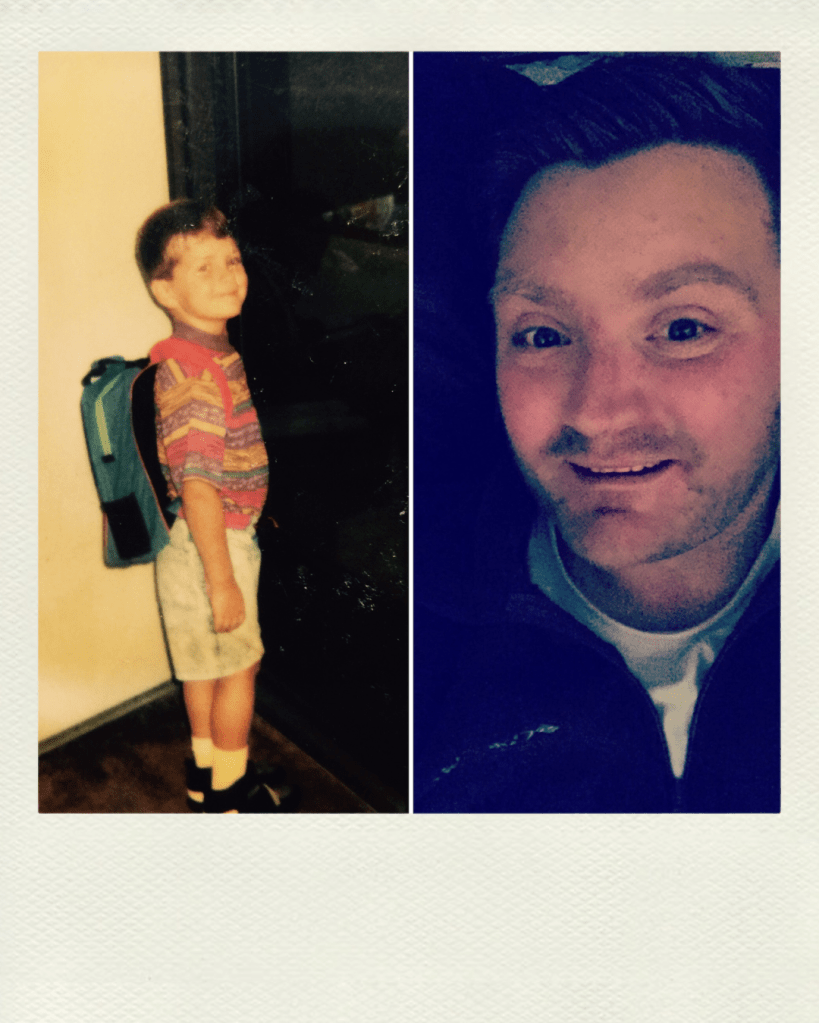

I have two “first day” pictures of school saved on my phone—one with a teal backpack and a forever‑wide nervous smile, the other with a stack of essays and the same crooked grin.

Left: me, Kindergarten, 1991, proud owner of a teal backpack and socks that did not match the shoes. Right: me on my first day teaching twelfth‑grade English at North Brunswick High, same smile, upgraded existential crisis.

I remember Miss Pamela Jackson’s classroom like it was lit from within—posters, crayon dust, the hum of chatter that made everything feel important. I was five, convinced a backpack could contain my whole future, and absolutely certain that school was where I belonged. Fast forward to North Brunswick, and the fluorescent lights hum a different song. My lesson plans were neat, my shirt probably wrinkled, and I rehearsed the opening line to my seniors like it was an incantation: “We are going to read, laugh, cry, argue, and maybe change one small thing about how you see the world.” I felt the same delicious, terrifying ache of possibility.

Why School Stuck With We:

There was something about the ritual—bell, backpack, lineup—that made life feel ordered in a good way. In Miss Jackson’s room, I learned that language could be a map to other people. That early feeling of being held by school is why I kept circling back to it, even when life tried to pull me elsewhere. Teaching felt less like a job and more like continuing a conversation that started when someone handed me a pencil and said, “Listen.”

The Messy Bits:

Of course, it wasn’t all perfect. The teal backpack didn’t save me from awkwardness, and my first year teaching didn’t spare me from the slow burn of mistakes—late nights grading, emails where my tone landed like a paper airplane, and the hit to my confidence when I realized my “big ideas” sometimes landed like homework nobody handed in. There were moments I wanted to quit, to stop being the person who cared so much that it hurt. But those messy, human moments are part of the story too—proof that loving something doesn’t mean you love it without scars.

What Teaching Gave Back:

In return, teaching returned a million small miracles—students who read a line and lit up, the exact wrong joke that made a whole class relax, the rare note from a grad years later saying, “You mattered.” It taught me patience with my own growth and the ability to hold contradictions: fierce optimism right next to bone‑deep tiredness. Also, it gave me an appreciation for shoes that can survive a classroom and still look like you tried.

Let us talk about the socks situation in the kindergarten photo. A bold choice. That teal backpack had more confidence than I did, accessorizing like it owned the playground. And grown‑up me in the teacher selfie? Same smile, slightly more resigned, pinch of coffee, and definitely fewer mismatched socks, but the same unstoppable optimism. If Miss Jackson could see me now, she’d probably smile, hand me a sticker, and then ask if I’ve read anything good lately.

Standing across those two images, what feels wild is how steady the center of me is—the part that loves stories, that wants to make space for curiosity, that thinks a well‑placed sentence can do something gentle and dangerous at once. First days are secret rituals of possibility, whether you’re five with a backpack or thirty‑something with a stack of essays. I still show up with that same wide, nervous smile, ready to be surprised.

If you’ve got a first‑day photo that’s been hiding in your camera roll, send it my way or drop a line about a teacher who changed you—I’ll read every single one.

Leave a comment